Art and physics: different as night and day, right?

True, the fundamental physical properties of matter come into play as artists work with their materials. But beyond that, what connection can there be between quantum theory and three sheets of carefully cut handmade paper, or a delicate piece of needlework?

In fact, there are some surprising similarities and even an underlying parallel in the processes and practices of both artists and physicists.

The AVĺ„ņ÷≤Ņ Art Gallery‚Äôs latest exhibition "A Very Long Engagement," which runs until this Sunday, highlights these similarities. The show features a variety of textile media: from familiar materials like paper and wool to some more unusual ones like sausage casing and metal. Jordan Kyriakidis, associate professor of physics at AVĺ„ņ÷≤Ņ, shared his thoughts on a couple of the pieces and how they relate to his own research practice.

As a quantum physicist, Dr. Kyriakidis deals with bits of matter so small they can’t be seen. So, does he mentally visualize the concepts he’s working with as he’s working? And if so, how?

‚ÄúHow I visualize things is very abstract,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs not in terms of equations or language. I‚Äôm not even sure it‚Äôs an image. It‚Äôs almost more like‚Ķ processes.‚ÄĚ

Looking for patterns in time and space

The idea of process relates perfectly to a triptych of works on paper by Jozef Bajus. Subtle yet beautiful, Prayers for Jacqueline #1, #2, #3 (2011) is comprised of three sheets of oatmeal-coloured Japanese kozo paper, each resembling a basic grid or x-y axis.

The middle of the first sheet of paper has been sliced vertically at three-millimeter intervals. In the second, alternating thin strips of paper have been removed then knotted around an attached strip. But it‚Äôs challenging to see any pattern ‚Äď or even where the paper was knotted ‚Äď because of the strips‚Äô overlapping loose ends.

The third is similar to the second, except that the ends of the tied strips face the wall, not the viewer. And in the second and third pieces, the knotted strips reveal that the verso side of the sheet is red and flower-patterned.

‚ÄúOne thing I like about this is that it deals with processes as well as the physical arrangement of the objects,‚ÄĚ Dr. Kyriakidis says. ‚Äú[Physicists] think about things in terms of processes and space and time, and often it‚Äôs very hard to disentangle them from each other.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúThat‚Äôs what [the Bajus piece] reminds me of, because it‚Äôs almost like snapshots frozen in time,‚ÄĚ he says. Yet there‚Äôs also a reference to space, especially in the second and third panels, in which the knots or ‚Äúcoordinates‚ÄĚ seem to move from front to back.

Work in progress

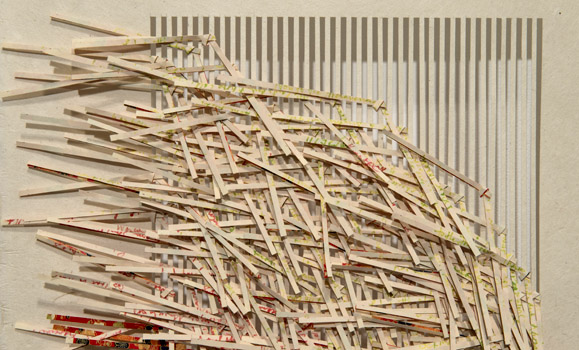

On the opposite wall is Working Drawings, a dozen or so mixed media images on wood by Doug Guildford. Each features outlined abstract forms and washes of opaque white and smudgey pale peach, reddish-pink, blue, and grey.

‚ÄúHere, too, I can see elements of what we do.‚ÄĚ Dr. Kyriakidis speaks again of the difficulty of creating a language others will understand. But it‚Äôs also about whether an idea ‚ÄĒ a hypothesis ‚ÄĒ ends up working.

First, Dr. Kyriakidis constructs ‚Äúa kind of a scaffold. Then, see if everything fits inside that structure.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs clear what a good structure is,‚ÄĚ he explains, ‚Äúand what semantics we‚Äôre putting on that structure. And it‚Äôs also clear when things don‚Äôt work. But what‚Äôs not clear is why they don‚Äôt work. Because the scaffolding we constructed was the wrong kind? Or, did we use the wrong semantics? That part is hard to distinguish.‚ÄĚ

It sounds frustrating ‚Äď and he concedes it is: ‚ÄúDoing research requires a certain temperament. You have to be comfortable with not knowing ‚Äď you have to be okay with having doubt pretty much all the time.‚ÄĚ

And all that, Dr. Kyriakidis thinks, is ‚Äúsimilar to how I imagine artists work: they want to express something, but they don‚Äôt know how exactly. And if it‚Äôs not working, they don‚Äôt know if it‚Äôs because the medium is wrong, or if it‚Äôs because the whole idea is stupid. But they do know when they ‚Äėget‚Äô it.‚ÄĚ

He notes that Working Drawings speak to that process: ‚ÄúEach is different, but there are similarities ‚Äď there‚Äôs always some line or pattern, a circle, a grid, in every one. It‚Äôs almost like the artist is trying to figure out what they‚Äôre trying to do.‚ÄĚ

The uncertainty principle of the thing

Works by Dorie Millerson further encourage discussion about uncertainty ‚ÄĒ both the uncertainty principle, and the uncertainty of knowing whether the results of one‚Äôs work will be successful.

Along one wall are suspended delicate, two-dimensional works of handmade lace: one depicts a pair of figures, while the other is an abstract hand. Two small spotlights, aimed slightly downward, cast shadows of the pieces on the wall behind.

How do these works relate to physics? ‚ÄúIn classical physics, there‚Äôs this big dichotomy between particles and waves,‚ÄĚ Dr. Kyriakidis begins. ‚ÄúOne way to express the uncertainty principle is that an electron can be both a particle and a wave.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúA comical analogy that I use is [to] imagine there‚Äôs a person, and every time you see him, you slap him on the head. Every day: boom, boom, boom. And then you say, ‚ÄėMan, that person is so cranky! He‚Äôs not a very nice person at all,‚Äô‚ÄĚ Dr. Kyriakidis says with a chuckle.

‚ÄúAnd then there‚Äôs this other person that you always hug, and you say, ‚ÄėOh, what a great person!‚Äô So what you do matters ‚Äď it‚Äôs not that he‚Äôs actually cranky, you‚Äôre making him cranky.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúSo, a photon is both a particle and a wave. You force it to be either, depending on what you do to it. That‚Äôs what I was reminded of when I saw these [needle lace pieces]: there‚Äôs a light, and there‚Äôs the actual object, and there‚Äôs a shadow, so which one is ‚Äėthe thing‚Äô?‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúSo, maybe it‚Äôs all of those,‚ÄĚ he adds. ‚ÄúYou see different aspects of it depending on what you focus on.‚ÄĚ