Carved into the limestone base of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in northern France are 11,285 names, one of which is Glenn Stephens Ells. The massive monument ŌĆö situated on a large swath of land where Canadian troops fought some of the most intense battles of the First World War ŌĆö was built as a tribute to soldiers such as Ells who lost their lives in the fighting and whose final resting place remains unknown.

Nearly 5,000 kilometres away in the village of Bible Hill, Nova Scotia, EllsŌĆÖs name is inscribed on another memorial ŌĆö this one smaller in scale and scope, yet no less meaningful as a tribute.

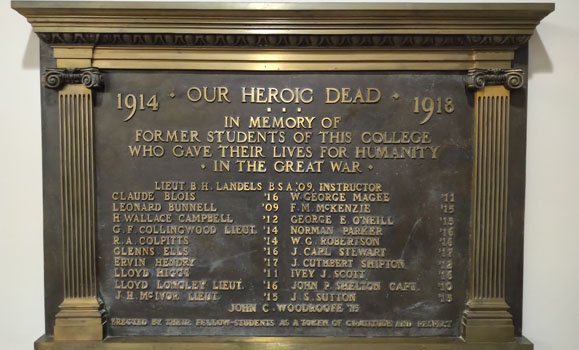

ŌĆ£Our heroic dead: In memory of former students of this college who gave their lives for humanity in The Great War,ŌĆØ reads the solid cast-bronze plaque that hangs today in the lobby of Cumming Hall on DalŌĆÖs Agricultural Campus.

EllsŌĆÖs name appears on the tablet alongside the names of 21 other former students and an instructor of what was then known as the Nova Scotia Agricultural College (NSAC), all of whom were killed or died in the fight against Germany and its allies.

The collegeŌĆÖs alumni association commissioned the plaque at its first meeting in 1919. More than a century later, it still serves as a potent reminder of the thousands of young Canadians, like Ells, who never had the chance to see where their education could take them.

Ells features in the left column on the bronze plaque in Cumming Hall.

A change of plans

A farm boy from the Annapolis Valley, Ells set out to follow the family path in agriculture after high school when he enrolled as a student at NSAC.

He explored a range of subjects during his first year of study, from entomology and animal husbandry to commercial law and mathematics. And as some notes jotted down on the back of one of his exam papers from the time show, he was also an avid hockey player with an interest in game strategy.

Like so many other young people at the time, though, EllsŌĆÖs life was about to be upended by the outbreak of war in Europe.

By 1915, the war on the western front in France was in full tilt and young Canadians were desperately needed on the frontlines. Ells signed up and first served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

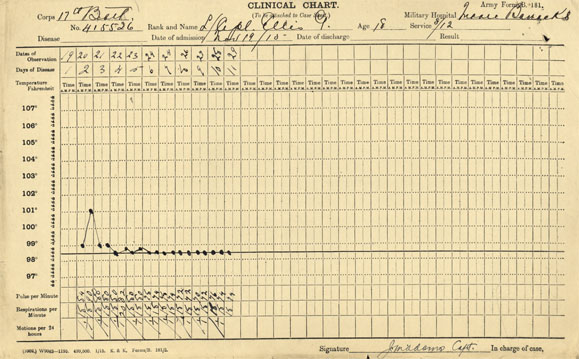

One of the most substantial battles Ells fought during his first year abroad was one for this own health. In late November 1915, just months after heŌĆÖd deployed from Canada, the 18-year-old was admitted to a military hospital in England with a fever hovering around 100 degrees. A clinical chart shows Ells spent close to two weeks fighting influenza and the high temperatures, vomiting and racing pulse that came with it.

Ells's clinical chart tracks his bout of influenza in late 1915. (Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation archives)

Into battle

The following March, Ells ŌĆö by now long recovered ŌĆö was transferred to the 5th Canadian Machine Gun Company and sent to Belgium, where he and his fellow troops billeted for a time on a farmstead.

ŌĆ£The sun is shining and birds are singing, and all reminds me of a spring Sunday at home except away to my left is the roar of the guns,ŌĆØ Ells wrote in a letter to his family that April.

The letter, while short, reveals a young man trying to stay positive even while itŌĆÖs clear heŌĆÖd rather be working the land than scoping out enemies.

ŌĆ£I miss home now. The air is so spring-like and I am billeted on a farm, anything to take the team and go out ploughing or any other work,ŌĆØ he writes. He describes the barn where they are sleeping as ŌĆ£something like the ŌĆśoldŌĆÖ barn at home.ŌĆØ

Elsewhere in the letter, he turns his attention more to the serious ŌĆ£workŌĆØ of the conflict at hand ŌĆö sharing how a general said ŌĆ£we have the best company over here in either division."

ŌĆ£I am well as can be and in good spirits. I donŌĆÖt mean by that that I am in love with my work, but am making the best of it.ŌĆØ

Ells concludes the letter to his father with some words of appreciation for the livestock: ŌĆ£You can picture us now in the haymow above the cows, eight pretty decent-looking ones. Now good-night. With love for you all. From your loving son.ŌĆØ

Ells would not have the chance to see his father, family or the ŌĆśoldŌĆÖ barn in Sheffield Mills, N.S. again. Just half a year later on September 28, 1916, at the tail end of the months-long Battle of Somme, Ells died in battle at Courcelette, France.

Read the full text of Ells's letter to his father below (reprinted in ):

In the Billets in Belgium, April 2nd, 1916

Dear Father;

This is a perfect day, the air and everything just like May at home. The sun is shining and birds are singing, and all reminds me of a spring Sunday at home except away to my left is the roar of the guns. It does not seem so hard to fight on a dull or disagreeable day, but on one like this it seems so out of place to have war. Gee! But I miss home now. The air is so spring-like and I am billeted on a farm, anything to take the team and go out ploughing or any other work. The old man here is at that now. He has a three-furrow gang plow and a pair of fairly good-looking horses. It looks like a good farming country if it ever gets dry. There are no stones at all. I have not seen a stone except on the roads.

There are hardly any people left where we are but some of the poorer class.

These Belgians have a queer way of driving their horses. The bridle rein is just like our working bridle only there is a single rope fastened to it, and he drives a pair by one rope. The tope on the off horse is tied to the wagon, and he was along driving by the one rope.

We have a very comfortable billet in an old barn. There are three sort of storeys to it, something like our ŌĆśoldŌĆÖ barn at home. I am on the higher scaffold, over the cows. There is some hay in it, enough to sleep on comfortably and it is quite warm, altogether, a good billet. There is a family in the house and the Sgt. Major and Quartermaster Sergeant stay there. One of the Generals said we have the best company over here in either division. It was not to us he said it, but I think we can keep up the name if we try. We have, in this company, only had one casualty in the last month, and that not a serious one. I am only a private now, as all our non-coms officers had to revert when they came over here. I am rather glad as I do not want responsibility for any other than myself, as I know hardly anything about the real work.

I was up and saw some of the boys of the 25th Battalion who are in billets a little way from us. I saw Ed Dickie, Scot Eaton, Glen Blenkhorn and some of the boys from Canning. They are all looking and feeling fine.

We can hear the guns (artillery) and see the shells bursting in the air, when the Huns are shooting at our aircraft.

Tell Mother we are fed pretty well, and everything is better than I pictured it, only a fellow has to pay about double for everything extra we buy. I am well as can be and in good spirits. I donŌĆÖt mean by that that I am in love with my work, but am making the best of it. We get a bath every week. Yesterday we marched up two miles for one, and it was sure good to get it. We turn in our dirty clothes, socks, towels and get fresh ones. We have some pretty good singers in our hut. Last night they sang until nearly twelve. We get our mail here every day. I got a box of fudge from Truro the other day. It sure went good. It is hard to make my letters very interesting, as there are so many things we must not tell. There are several old windmills near here and all going. This is all for now as it is bedtime. You can picture us now in the haymow above the cows, eight pretty decent-looking ones.

Now good-night

With love for you all

From your loving son